When Your Co-Founder Is Your Best Asset—and Your Biggest Risk

Equity is cheap when your partner is a force multiplier. It’s brutally expensive when they’re a liability in slow motion.

There’s a saying in Spanish: “Cuentas claras conservan amistades.” Clear accounts preserve friendships.

I’d go further: clear accounts, clear roles, and a clear operating agreement can save your company—and your sanity.

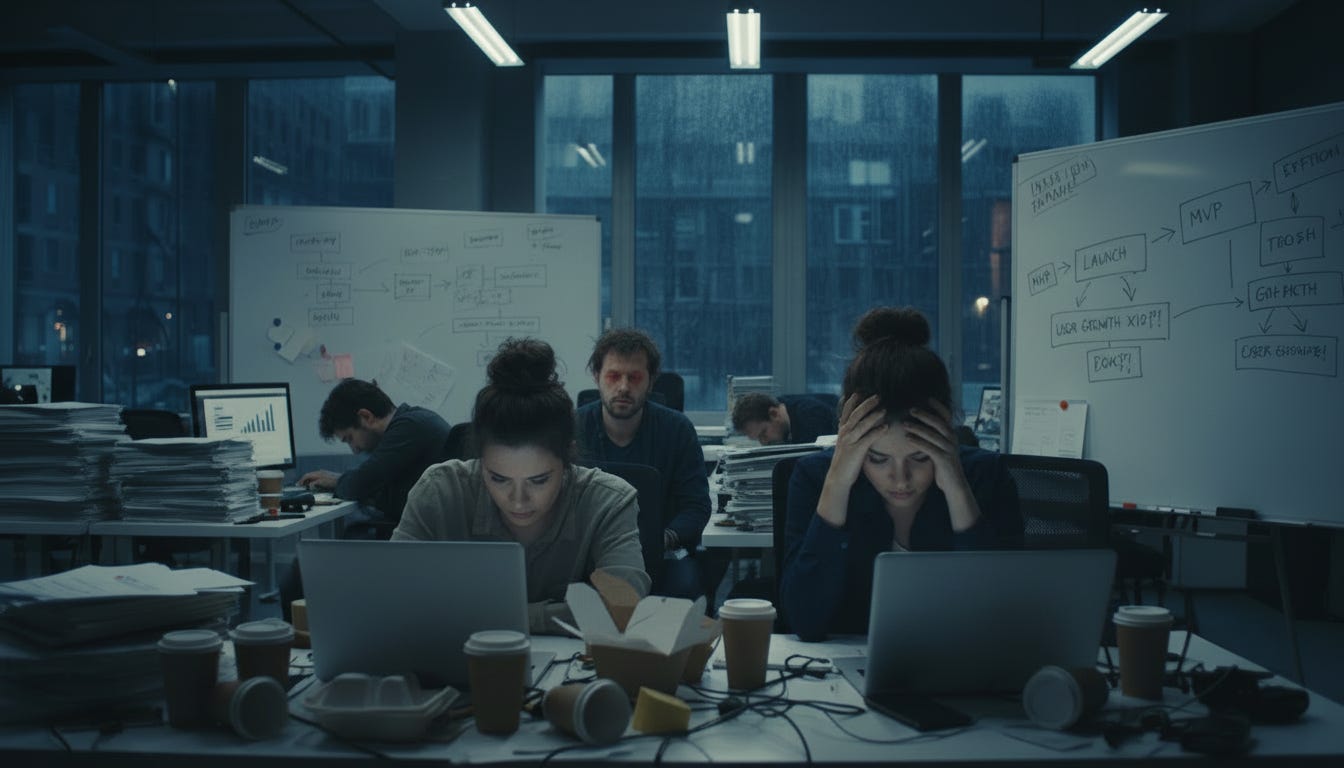

Founders love to romanticize the business partner. The person who “gets it,” who jumps off the cliff with you, signs the same guarantees, pulls the same all-nighters. When it works, a great co-founder is a cheat code. When it doesn’t, that same person becomes a quiet, compounding risk to everything you’ve built.

This is a story about both sides.

When a partner is a superpower

Let’s start with the good version, because it does exist.

A great partner is the one who:

Shows up when things break, not just when press releases go out.

Takes the unsexy work seriously, not just the flashy stuff.

Holds you to your stated standard, not the convenient standard of the week.

Tells you, “You’re wrong—and here’s why,” without making it personal.

If you’ve ever built something real, you know the feeling. You send a horrible update—bad numbers, bad news—and your partner replies with: “Okay. This sucks. Here’s how we fix it.” Not blame. Not panic. Just commitment.

The right co-founder gives you emotional runway when financial runway is thin. They take the ugly investor call. Fire the person you’ve been avoiding. Renegotiate with the landlord. Admit the strategy you both loved is dead—and help you bury it without theatrics.

When that’s the dynamic, equity never feels expensive. You’re genuinely happy they own as much as they do, because without them, the company doesn’t work.

When the legend becomes the liability

There’s another version.

This is the partner who slowly begins to believe his own legend. The one for whom rules, processes, and deadlines are for everyone else. He’s “the boss,” so the calendar, the budget, and the agreements become… suggestions.

At first, you justify it.

“He’s stressed.”

“We’re all overwhelmed.”

“He just had a kid.”

“This is just how founders are.”

I’ve been there. Several times.

In one of my past ventures, a partner managed payroll. During our end of year routine audit—one of those boring, standard ones—we discovered he’d paid himself a higher salary for quite a few months. Not a rounding error. Not a typo. A full extra salary.

When questioned, the answer was immediate: “It was a tax mistake.”

Here’s the uncomfortable part: everyone knew that explanation wasn’t quite right. Maybe it wasn’t criminal mastermind stuff, but it wasn’t innocent either. And we did what founders so often do—we chose the story that allowed us to keep moving.

We let him “pay it back.” We told ourselves it was cheaper to keep the peace than to call it what it was: a breach of trust at the top.

That extra salary wasn’t the only issue. It was just the most measurable one and it was the beginning to a very long and uncomfortable journey that almost bankrupted us.

The real problem was the pattern:

deadlines missed, chronically

commitments made verbally, then forgotten

“I’ll send it tomorrow” messages that never became documents

rules broken because “I’m the founder”

None of these things, individually, looked big enough to blow up a company. Together, they eroded trust in a way that’s hard to reverse.

The cost of ignoring what you already know

Why do founders tolerate this?

Because confronting it feels existential.

If you’re honest about the problem, you have to ask scary questions:

What if he leaves? Who runs X? What will employees think? What will investors say if they sense drama at the top?

So you rationalize.

You downgrade a breach into a “miscommunication.”

You relabel a pattern as “a bad week.”

You avoid putting anything in writing, because writing it makes it real.

Meanwhile, the team notices. People aren’t blind. They see when one founder is held to a different standard. They feel the tension even when nobody names it.

Good employees quietly start looking. Vendors tighten terms. Partners get cautious.

That’s the real cost: not just the money that went missing, but the confidence that drains out of the system.

And by the time lawyers or auditors are in the room, your leverage isn’t your passion or your story.

It’s your paperwork.

The least glamorous hero: your operating agreement

This is where the operating agreement—usually treated like a boring formality—shows up as the main safety net.

When things are good, an OA is a PDF in a folder.

When things are bad, it becomes the only neutral voice in the conversation.

In our case, a proper operating agreement didn’t make the situation pleasant. But it made it survivable.

It:

spelled out how decisions were supposed to be made

defined what constituted “cause” and what the removal process looked like

described how compensation and distributions worked

provided a roadmap for what happens in a deadlock

We didn’t avoid conflict. We still spent time, money, and emotional energy resolving it. But the OA gave us something objective to point to when memories, interpretations, and WhatsApp screenshots didn’t align.

That’s the real function of an operating agreement: it remembers what you both agreed to when you still liked each other.

Have the hard conversation before you need it

If your partnership still feels like a honeymoon, this is exactly the moment to have the hard talks.

You don’t do it because you distrust your co-founder. You do it because you respect each other enough to plan for versions of the future where one or both of you are tired, broke, burned out, or simply different.

Talk—concretely—about:

Separation.

What happens if one of us wants out? Stops performing? Life changes—divorce, illness, kids, another opportunity?

Power.

Who has final say over what? What requires unanimous consent and what doesn’t?

Money.

How do salaries work? What’s the protocol for bonuses, distributions, or “temporary” over-payments? (Anything involving money needs to be in writing.)

Role drift.

What happens if I no longer want to do what I’m doing today? What happens when I’m no longer capable to do the role? Who makes the call? Can we bring in a CEO above us? Under what conditions?

Non-negotiables.

What behaviors are grounds for separation even if the KPIs look great? Lying? Hidden side deals? Harassment? You cannot handle these case-by-case after the fact.

Write the answers down. Sign them while you still assume you’ll never need them.

Because if you ever do need them, you’ll be grateful they were drafted by calm, optimistic versions of yourselves—not the angry, exhausted people you become mid-fight.

“Cuentas claras conservan amistades” isn’t just about accounting. It’s about expectations. It’s the difference between “I feel betrayed” and “We agreed this is how we would handle this.”

The range of outcomes

I’m not anti–co-founder. The lesson isn’t “never have a partner.”

The lesson is that founders underestimate the range of outcomes—because optimism is part of the job description.

In the beginning, everything feels fixable. Red flags look like “stress.” Patterns look like “a phase.” And your gut? You treat it like superstition instead of signal.

Here’s what’s annoying: my gut has been right more often than my spreadsheets. Every time I knew a partnership would work, it worked. Every time I had that low-grade dread that it wouldn’t, it didn’t.

I ignored it several times. The guy had left every job and every work relationship in bad terms. Consulting, franchises, partnerships… same movie, different cast. Every time it failed, the villain was a third party. I bought the story. I shouldn’t have.

On one end, the right partner is a multiplier. You build something 10x bigger because you cover each other’s blind spots, divide the emotional load, and compound strengths.

In the middle, a misaligned but functional partner quietly caps your growth. You design workarounds around their habits. The company becomes smaller than it should be.

On the far end, a bad partner can sink you—no matter how good your product, brand, or market is.

If the foundation is rotten, it doesn’t matter how pretty the building is.

The market you chose, the deck you send investors, the tech stack you use—none of it is as structurally important as who sits next to you on the cap table and what rules govern that relationship.

What I’d tell my past self

I know the rules of the game. In every company I’ve started and every one I’ve advised the last few years, I’ve tried to follow them.

But knowing the rules and enforcing them are two different skills.

Sometimes you have the operating agreement. Sometimes you even have the proof. And you still hesitate…because emotions show up wearing a friendship mask. You tell yourself you’re being loyal, when you’re really just postponing the inevitable.

If I could go back to an earlier version of myself—the one swallowing the “tax mistake” story and pretending everything was fine—I would have ended the business relationship right then and there. Not out of anger. Out of respect for the company. And honestly, for the friendship too.

So here’s the recap:

Your gut is a data source. If something feels off, treat that as information. You don’t need a spreadsheet to justify hard questions.

Don’t confuse loyalty with enabling. A second chance can be generosity. Building your entire operating system around someone’s worst habits is negligence.

If it matters, write it. Roles, salaries, clawbacks, deadlines, side deals—if you expect to rely on it in a crisis, it can’t live only in WhatsApp.

Professionalize early. Audits, basic governance, real reporting—they’re not “corporate.” They’re smoke alarms.

Design the breakup while you’re still in love. A solid operating agreement isn’t a sign you expect to fail. It’s a sign you’re serious about protecting what you’re building, even from yourselves.

And one last thing: a good lawyer is expensive, but you can’t overpay for a good one. If you truly can’t afford counsel yet, use templates, study best practices, pressure-test terms with mentors—do something. But don’t do the most dangerous version of entrepreneurship: two people, one bank account, and zero paper.

Your operating agreement isn’t pessimism—it’s insurance against your own denial.

I spend a lot of time thinking and writing about food, hospitality, tech, and capital. But none of that matters if you ignore this one decision: who you decide to build with—and how you structure that relationship.

Choose carefully. Write clearly. And if you’re already staring at red flags, stop repainting them yellow.